Experts now say that “IBS is caused by a disturbance in the way the brain and the gut interact.” This is true, but it fails to address the real issue and that is that the gut has its own brain. Yes, we have a “second brain” in our guts! This second brain is called the Enteric Nervous System, or ENS. IBS isn’t just a problem with the way that the gut talks to the brain, but with the ENS itself.

The Two Nervous Systems

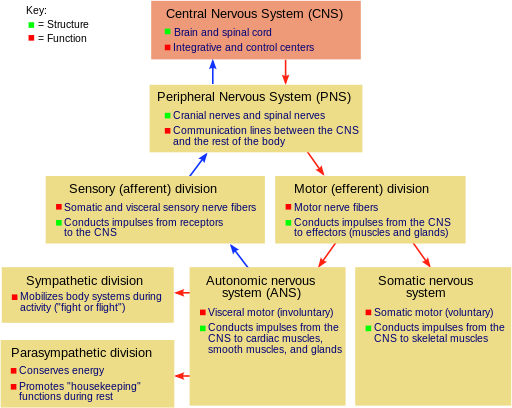

The nervous system is responsible for carrying signals throughout our body and it is often referred to the “command center” which keeps us going. So, it might come as a surprise that there is actually more than one command center.

The nervous system can be broken down into two parts:

- Central nervous system: Which includes the brain and spinal cord

- The Peripheral Nervous System: Which includes all of the nerves outside of the CNS

The PNS can further be broken down into:

- Somatic nervous system: In charge of voluntary control of muscles and sends sensory information to the CNS

- Autonomic nervous system: In charge the involuntary functions like motor and sensation response of our organs.

The autonomic nervous system is divided into three parts: the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system and the enteric nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system are responsible for the “fight-or-flight” response to stress. The parasympathetic NS is in charge of housekeeping functions during rest.

The enteric nervous system doesn’t get mentioned much, and it often isn’t even included in diagrams of the nervous system. However, the ENS – which is located in your gut — is incredibly important and is likely the root cause of IBS.

Image by Fuzzform; Found at Wiki Commons. GNU Free Documentation License

The Enteric Nervous System

The ENS is a division of the Autonomic NS, but it regarded as a separate nervous system which acts autonomously from the brain (though it is still connected to the brain and their functions are interlinked). The ENS is the only part of the peripheral nervous system which is capable of acting autonomously. It has about 500 million neurons, which is more than found in our spinal cord. To put this number in perspective, consider that a hamster brain has about 90 million neurons and a marmoset monkey brain has about 635 million neurons. (Source 1, 2)

The ENS is also the “original” nervous system. It developed in the first vertebrates over 500 million years ago, back when we were still just jawless worm-like animals sucking on rocks. Experts even believe that the brain probably grew from the ENS as it gained complexity and different roles. All vertebrates have an ENS as well as a CNS.

It makes sense that our guts would have a separate nervous system. First off, there is the evolutionary reason. Long before animals evolved to have complex thoughts, they needed a nervous system to tell them to eat.

Secondly, the gut needs its own nervous system because digestion is so complex. The gut really accomplishes an amazing feat when it takes food that we’ve consumed, breaks it down into useable parts which we absorb into the blood and then expels the waste we don’t need. To do all of this, the gut must be capable of moving in a very coordinated way. Even if a slight disruption occurs, you can have serious problems (as anyone with IBS knows).

The gut also is exposed to all sorts of potential dangers, such as harmful bacterial invaders which were consumed along with the food we eat. The gut is able to keep us safe from harm by using immune cells to locate these invaders and secrete inflammatory substances like histamine. The ENS picks up on the signals and triggers reactions like diarrhea to get rid of the harmful substance. When you consider this, it isn’t too surprising that 80% of our immunity is located in the gut. (Source 1, 2, 3, 4)

On a side note, I think it is worth mentioning that it was only recently that the importance of the ENS was discovered. We can thank Michael Gershon, MD for this. When he started doing his research into the ENS about 50 years ago, there was only one other person studying it. Gershon discovered that serotonin was present in the gut, which was a landmark discovery that showed the link between the gut and nervous system. Gershon is considered the father of neurogastroenterology, which is now a flourishing field with hundreds of researchers. In 1997, Gershon published the book “The Second Brain” (buy here) which talks about the ENS. (Source 1, 2)

The Role of the ENS

The ENS might be called our “second brain” or the “brain in the gut,” but it has a much more limited function than what our actual brains do. The ENS is primarily in charge of controlling digestion. While this role might not be as sexy as those of the brain, it is still very important. We wouldn’t be able to anything with these big brains of ours if the ENS didn’t allow us to take in nutrients from food.

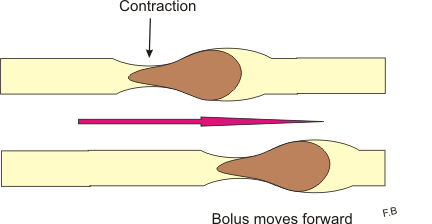

Of the many roles of the ENS in digestion, the most important for understanding IBS is regulating motility. Motility is the wave-like muscle contractions in the GI tract. There are two types of motility: peristalsis and the migrating motor complex (MMC).

Peristalsis is what propels food from the esophagus down into the stomach, gut, and finally to the rectum. You probably haven’t given much thought to how your food gets from one place to another, but it is actually really amazing. Your GI muscles have to be really coordinated to ensure everything goes right. For example, those muscles better make sure the “gateway” between your small and large intestine is opening up at the right time and closing properly. Otherwise, you can get undigested food in the large intestine, or have fecal waste backflowing into the small intestine. With IBS, peristalsis is not operating properly and a slew of problems ensues.

The other type of motility is the MMC. It occurs only after you haven’t consumed food for a while. These muscle contractions act like a housekeeper. They sweep through your gut to clean out any waste – including excess bacteria which shouldn’t be there. If your MMC isn’t working right, you can end up with SIBO, which could be the real cause of your IBS symptoms. (Source 1, 2) Upwards of 84% of IBS patients test positive for SIBO. Read more about SIBO here.

The Gut-Brain Connection

When doctors say that “IBS is in your head,” they are right in one sense. While it is mostly problems with the Enteric Nervous System which cause IBS (which is in your gut and not in your head!), the ENS communicates with your Central Nervous System and thus is very much in your head too.

The ENS of the gut communicates with the brain through the parasympathetic NS (via the vagus nerve) and the sympathetic NS via the prevertebral ganglia. (Source 1)

You don’t have to be a gastroenterologist to know that the brain and gut are connected. Just think about how you get butterflies in your stomach when you are worried or stressed. For a long time, scientists thought the gut-brain connection was a one-way street and hence why GI conditions like IBS were written off as being caused by stress. Now, scientists are realizing that the gut’s nervous system is actually a lot more powerful than could have been imagined.

For example, scientists were shocked when they found that 90% of the signals going through the vagus nerve did not originate from the brain but rather came from the ENS. Another shocking discovery was that, when the vagus nerve is severed, the ENS can continue functioning. In this way, the “brain in the gut” has an enormous influence on us. Researchers in the new field of neurogastroenterology are finding evidence that gut disorders may be the root cause of problems ranging from obesity to autism. (Source 1, 2)

This doesn’t mean that problems originating in the central nervous system won’t also affect digestion and cause problems like IBS. However, we shouldn’t say that gut problems like IBS are a problem with “gut-brain” communication when the gut’s own nervous system is the one mostly in charge.

Do you have IBS? Download our free guide 7 Things You Wish Your Doctor Told You About IBS.

Latest posts by Sylvie McCracken (see all)

- Treating H. Pylori (Part 3): What H. Pylori Does to the Body - August 8, 2022

- Treating H. Pylori (Part 2): How H. Pylori is Contracted - August 3, 2022

- Understanding Beef Labels: Organic, Pastured, Grass-Fed & Grain-Finished - July 25, 2022